Invention turns cell phone into mobile medical lab

By Steve Almasy, CNN

When Debbie Gordon and her fellow health-care mission workers go to Belize, there's just so much they can do to treat people in the remote village of Gales Point.

Her group, which includes two or three doctors, can only treat the town's 300 villagers based on the symptoms patients describe or what the doctors observe.

"If we had the ability to take a device that could do field tests and get back the results in a few days, that would be very helpful," said Gordon, a health educator based in North Carolina, who teaches doctors and nurses about care for sick newborns.

How about in a few seconds? Such a device may be available in the near future, and it could turn a cell phone into a mobile medical lab -- and change the way doctors treat patients in rural areas far from hospitals.

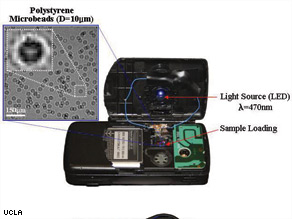

Professor Aydogan Ozcan of UCLA has taken a typical Sony Ericsson phone, and by adding a few off-the-shelf parts that cost less than $50, he can get it to produce a remarkable image that shows the thousands of cells in a small fluid sample such as human blood.

"It is a new way of doing images of cells and bacteria," said Ozcan, an assistant professor in UCLA's electrical engineering department. While other small imaging systems use bulky optics, his group's invention offers "true miniaturization of a laboratory" because there are no lenses and the results are quick and accurate, he said.

The device is called LUCAS, which stands for lensless ultra-wide-field cell monitoring array platform based on shadow imaging. It uses a short wavelength blue light to illuminate a sample of liquid -- blood, saliva or another fluid -- on a laboratory slide.

LUCAS captures the image to a chip in the cell phone. If the phone is loaded with an algorithm program, it then counts the microparticles much faster than a human can. The image also can be transmitted wirelessly to a computer, which analyzes it and sends back a text message with the results.

For instance, CD4 counts -- or the measure of T cells in a person's blood -- can determine if an HIV patient has AIDS. Or a red cell count can help determine if a patient is anemic or might have malaria.

Ozcan compares the images to the shadows you see when you walk down the street on a sunny day.

"These cells also have a shadow, but their shadows are not like our black shadows, they are much more rich," he said.

The holograms produced by the camera are fuzzy and cannot be read by the human eye. Doctors still need microscopes to examine a sample from a patient.

The cells are different in shape by type, so the LUCAS system counts the cells using an algorithm developed by the UCLA team. Ozcan said the report generated is 90 percent accurate.

The test is not meant to replace sophisticated optics. But the device could offer a fast, preliminary diagnosis in hard-to-reach areas such as remote villages in sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV rates are the highest in the world.

"What makes it quite valuable is that it is small and inexpensive," said Skip Garner, professor of Biochemistry and Internal Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas. "It's also the scientific proof of a principle in its very early stages. Once the group puts more and more work into it there are going to be a huge number of applications that are going to come out."

Ozcan said he came up with the initial concept about two years ago. Major improvements have come in the past 18 months, but the system is still considered a prototype, he said. In the future if the LUCAS is built into a smart phone or similar hand-held device, it would add only a few dollars to the cost, he said.

Ozcan also wants to further develop LUCAS' imaging capability to record events at the molecular level.

"We want to go now from microscale to nanoscale," he said. "We want to detect DNA fragments or protein."

Garner wonders whether the device could differentiate between similar-looking bacteria. There is good E. coli and bad E. coli, for example, and they are almost identical in structure.

Ozcan's team is also still trying to understand the density limits of LUCAS. When there are many cells in a sample, it becomes harder to count them all, Ozcan said.

"But if you are looking for a diseased person, it's not usually the count [that is important] but the morphology of the cells," he said.

Another potential pitfall is the lack of cell-phone coverage in remote areas. But many Third World countries are developing cellular networks, Ozcan said.

Gordon, who has made several mission trips to Belize, says a device with the LUCAS system would be ideal for her team. There are no doctors in Gales Point, so her group's visit is one of the few times medical professionals come to the village.

The nearest hospital is more than 90 minutes away.

"To get results right away would be phenomenal," she said. "I'd want to test every villager on my next trip."

Source: CNN